In an ironic twist, in August, election observers fell under scrutiny when Kenya’s Supreme Court declared the presidential vote invalid - after most monitoring groups said the polls were genuine. This isn’t the first time election observers have come under criticism. Scholars like Thomas Carothers were criticizing what he called “amateurish work” as far back as the late 1990s. Others, like Judith Kelley, have looked at how different monitoring organizations have observed the same elections, but reached quite different conclusions. Her research suggests that observers are more likely to endorse elections where the country is a foreign-aid recipient or where the election observers are part of missions from inter-governmental organisations, like the European Union (EU) or the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE).

I’ve always been interested in this question. In theory, election observers should adhere to the Declaration of Principles for International Election Observation, a document that lays out specific guidelines for their behaviour. Nearly all of the most reputable organizations follow these guidelines and their reports are highly diplomatic texts, for good reason. Research has shown that the mere presence of observers can deter or displace fraud and reduce the likelihood of election-related protests.

Can we use text mining to tell us more about how election observers write about elections? What words are used the most? What is the average sentiment of reports? Is this different for the type of election (parliamentary or presidential)? Does sentiment analysis work - that is, does it reflect whether or not the observers endorsed the election?

Warning: There’s a ton of R code below, so if you’re more interested in the analysis, scroll down further.

Getting the data

To start, I went to the OSCE website and used their internal search engine to find the election observation reports of the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR), which is the arm of the OSCE that observes elections. The first page of results gave me only 50 reports and I scraped all of those links (and the following two pages by repeating the code - not very efficient, I know).

library(rvest)

library(stringr)

library(lubridate)

library(tidyverse)

library(tidyr)

library(robotstxt)

library(pdftools)

library(hrbrthemes)

library(scales)

osce_reports <- read_html("http://www.osce.org/resources/documents/%22Final%20Report%22?page=1&filters=%20im_taxonomy_vid_3%3A%28120%29%20im_taxonomy_vid_1%3A%2824%29%20im_taxonomy_vid_22%3A%28472%29&solrsort=score%20desc&rows=50&category=Official%20Documents")

osce <- read_html("http://www.osce.org")

#get links to the English language PDFs

links <- osce_reports %>%

html_nodes(".active") %>%

html_attr("href")

#cast list as dataframe - I am pretty sure I could do this in a better way

links_df <- do.call(rbind, lapply(links, data.frame, stringsAsFactors=FALSE))

#rename the first column

names(links_df) <- "url"

At this point, I noticed that in getting the links to the PDF reports, I also grabbed a lot of extra links that I didn’t need. In the next step, I had to filter out all of that junk.

#create a new column that has a logical value depending on whether or not the URL is to a downloadable report

links_df$report <- grepl('download=true', links_df$url, ignore.case=TRUE)

#keep only rows with TRUE value

links_df_subset <- links_df[links_df$report==TRUE, ]

#create full links

links_full <- paste("http://www.osce.org", links_df_subset$url, sep = "")

I was nearly ready to begin scraping the PDFs, but I checked first what the OSCE site says about scraping by using:

robotstxt::get_robotstxt("http://www.osce.org")

This showed a crawl delay of 10 seconds, so I set that as the sleep time between downloading each PDF.

#loop to download reports

for (url in links_full) {

download.file(url, destfile = basename(url),

Sys.sleep(10))

}

I did this a few more times and ended up with 141 election reports after deleting any duplicates. (Note: From going through Stack Overflow questions, I’m pretty sure I could have also set this up to scrape all the search results pages, but I wasn’t quite ready to make the time investment).

There was one rather big problem with my approach though. I would need to read the PDF files into R in such a way that they could be associated with my variables of interest (country, type of election, and year). Since I had downloaded the files using the basename of their URLs on the OSCE site - and the filenaming conventions for these PDFs were a mess - this left me a lot of work to do with manually renaming the files. In the end, I settled on a filenaming system that looked something like this: “myanmar_parl2015.pdf”. This way I could read the files into R using the filename as a variable, and create additional variables based on the filename - an approach I figured out using this excellent answer on Stack Overflow, by one of the developers of tidytext, Julia Silge.

#list all files ending with extension .pdf

files <- list.files(pattern = "pdf$")

#read all PDFs and unnest them using tidytext, adding a filename variable

osce_reports <- map_df(files, ~ data_frame(txt = pdf_text(.x)) %>%

mutate(filename = .x) %>%

unnest_tokens(word, txt))

#add 'type' column based on the text in the filename column

osce_reports$type <- ifelse(grepl("pres", osce_reports$filename, ignore.case = T), "President",

ifelse(grepl("parl", osce_reports$filename, ignore.case = T), "Parliament",

ifelse(grepl("local", osce_reports$filename, ignore.case = T), "Local",

ifelse(grepl("ref", osce_reports$filename, ignore.case = T), "Referendum",

ifelse(grepl("general", osce_reports$filename, ignore.case = T), "General", "Other")))))

#extract years and country names from filename varaible, and create additional variables

pattern_year <- "(\\d)+"

pattern_country <- "[^_]+"

osce_reports$year <- str_extract(osce_reports$filename, pattern_year)

osce_reports$country <- str_to_title(str_extract(osce_reports$filename, pattern_country))

#add an 'organization' column specifying the organization

osce_reports$organization <- "OSCE"

#finally, convert the 'year' column to POSIxct

osce_reports$year <- as.Date(paste(osce_reports$year, 1, 1, sep = "-"))

I finally had a dataframe as a “one-row-per-term document” for tidy analysis.

# A tibble: 1,171,527 x 6

filename type year country word organization

<chr> <chr> <date> <fctr> <chr> <chr>

1 uzbekistan_pres2007.pdf President 2007-01-01 Uzbekistan 2.85 OSCE

2 uzbekistan_pres2007.pdf President 2007-01-01 Uzbekistan 420,815 OSCE

3 uzbekistan_pres2007.pdf President 2007-01-01 Uzbekistan 434,111 OSCE

4 uzbekistan_pres2007.pdf President 2007-01-01 Uzbekistan 88.10 OSCE

5 uzbekistan_pres2007.pdf President 2007-01-01 Uzbekistan liberalisation OSCE

6 uzbekistan_pres2007.pdf President 2007-01-01 Uzbekistan approprate OSCE

7 uzbekistan_pres2007.pdf President 2007-01-01 Uzbekistan 2,5 OSCE

8 uzbekistan_pres2007.pdf President 2007-01-01 Uzbekistan akhtam OSCE

9 uzbekistan_pres2007.pdf President 2007-01-01 Uzbekistan commission63 OSCE

10 uzbekistan_pres2007.pdf President 2007-01-01 Uzbekistan diloram OSCE

# ... with 1,171,517 more rows

In the interest of time - and to get to the analysis - I’m going to skip the code that I used to get the data for EU Election Observation Missions and two US-based non-governmental organizations, the National Democratic Institute (NDI) and the International Republican Institute (IRI). In the end, I retreived 76 EU election observation reports, 34 IRI reports, and 17 NDI reports. In total, I now had 268 election observation reports for elections in 100 different countries between 1997-2017. Great! I also now had a pretty large dataframe with 3,056,4480 observations.

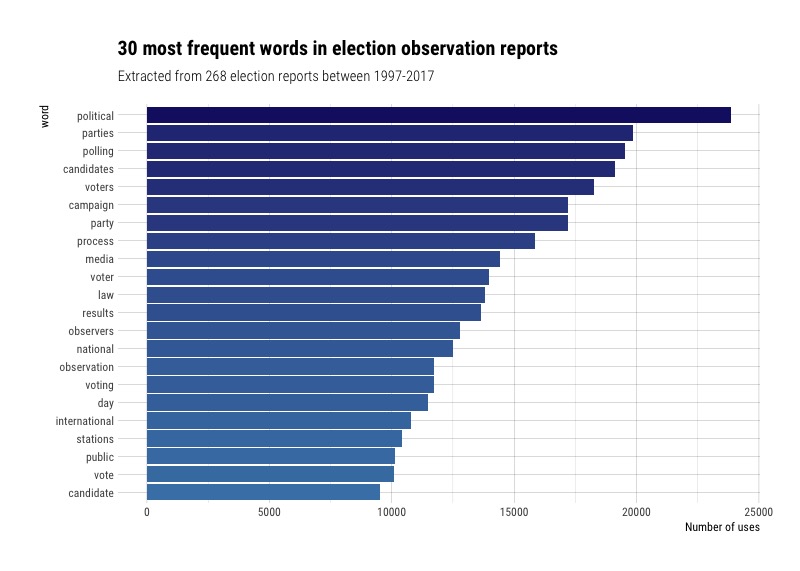

Let’s see which words are used the most often in election observation reports. After removing stop words and other words referencing organizations (“eu”, “osce”, “odihr,” “eom”, “iri”, and “ndi”) as well as less interesting words (“elections,” “electoral”, etc.), I had the following bar chart.

This is interesting because some of the most common words allude to specific issues related to elections, like political parties, candidates and campaigning; polling and the release of results; and voting and election day.

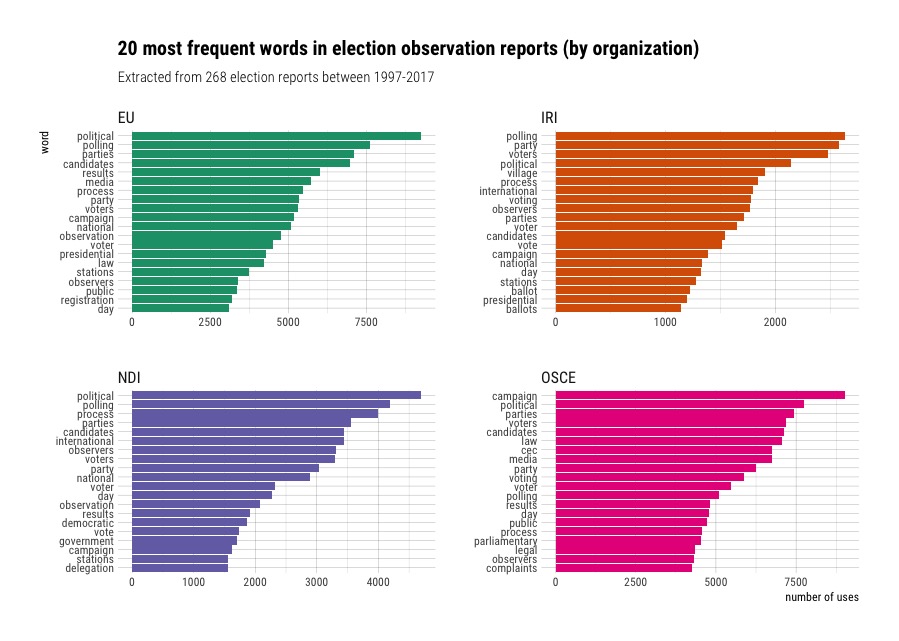

We can also facet by the organization type and see which words were the most common for each organization.

We can see slight differences in the most common words, but not very much. The OSCE words are perhaps the most distinctive, with terms like “parliamentary,” “complaints,” and “legal.” “Polling,” “political” and “parties” are the most frequent in some combination for all reports, with some organizations having distinctive words like the EU’s (voter) “registration” and IRI’s “ballots.”

Which human rights treaties do election observers reference?

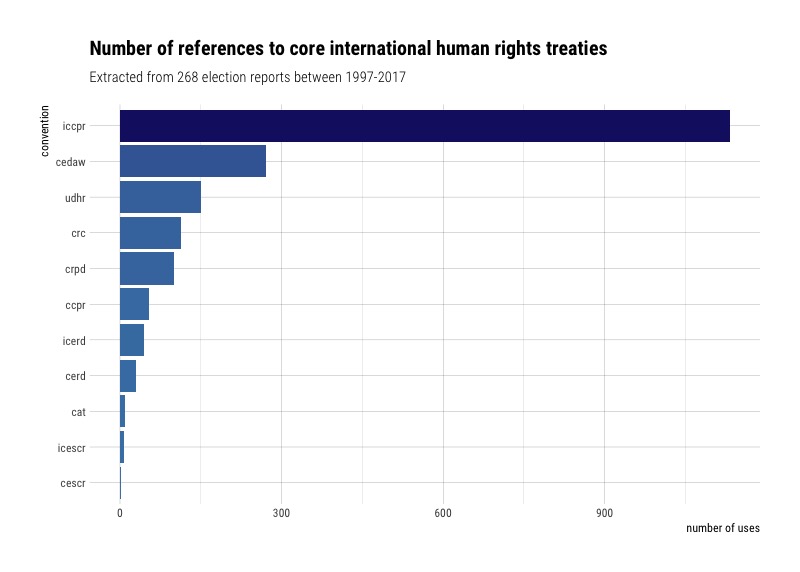

Election observers use international law as a standard to measure the quality of elections. This means assessing different elements of an election against the international obligations that a country has committed to fulfill, particularly by treaty ratification. The most relevant international treaty for elections is called the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which 169 countries have ratified. The ICCPR covers basic rights like the right to stand for elections, the right to secret and universal voting, and freedom of association, among other rights. Can we look at the election observer reports to see which treaties they mention the most in their reports?

Unsurprisingly, the ICCPR is the most referenced treaty. Next is the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). I have to admit that the last one surprised me.

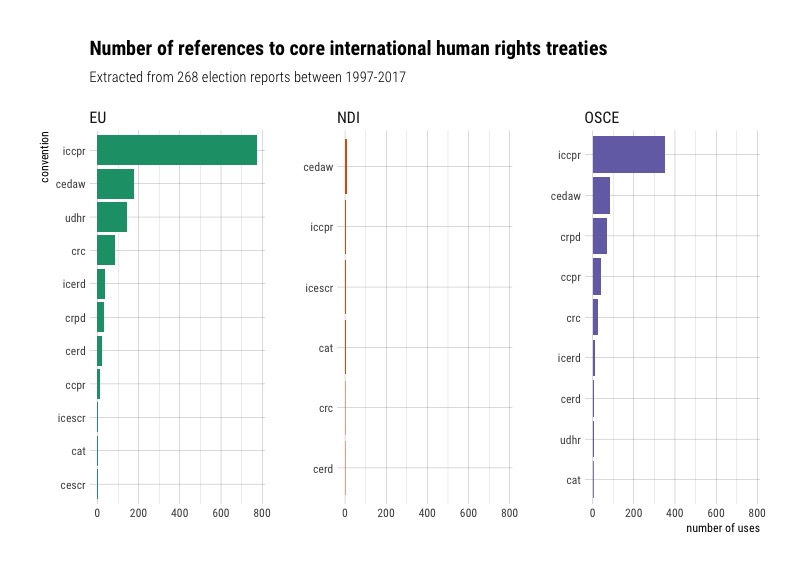

We can also facet by organization to see which ones mention these treaties the most.

Intergovernmental organizations seem to refer to treaties the most (but this data is slightly skewed since we have more IGO reports to draw on), with the EU using the most references, despite having less reports than the OSCE. One distinction is that the EU references the UDHR far more than the OSCE, and the OSCE references the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD)more. The OSCE also never mentions the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR). In IRI reports, there seem to be no references to international conventions.

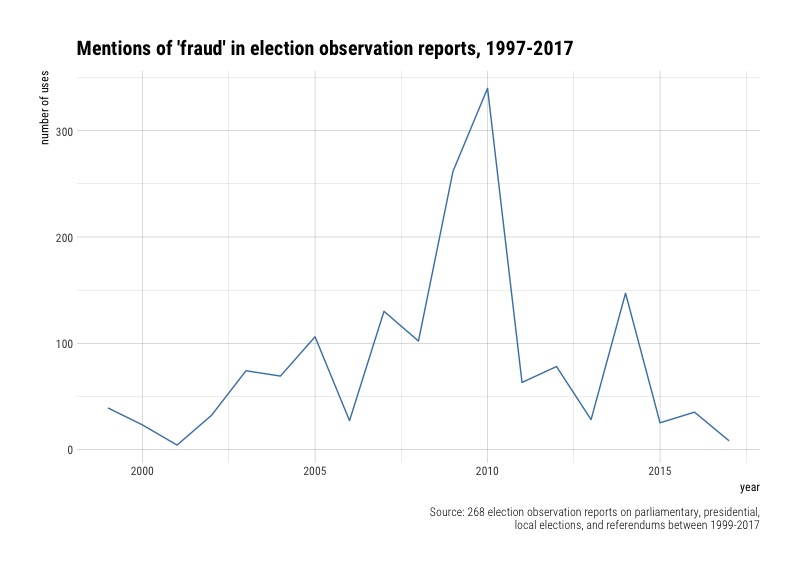

How often do election observers use the word “fraud”?

Election observers are generally cautious about leveling allegations of electoral fraud, so how often do they use the term in their reports?

There are relatively few references to fraud in almost two decades worth of reports. But there were three years where mentions of fraud were quite high, in 2009, 2010, and 2014. What elections might have contributed to this?

# A tibble: 153 x 3

# Groups: year [19]

year country word

<date> <chr> <int>

1 2010-01-01 Afghanistan 264

2 2009-01-01 Afghanistan 184

3 2014-01-01 Afghanistan 114

4 2007-01-01 Nigeria 71

5 2003-01-01 Nigeria 60

6 2004-01-01 Philippine 56

7 2005-01-01 Liberia 41

8 1999-01-01 Ukraine 39

9 2005-01-01 Afghanistan 39

10 2008-01-01 Bangladesh 39

# ... with 143 more rows

The 2009, 2010, and 2014 elections in Afghanistan were marred by ballot stuffing and other forms of fraud (this is an aside, but for a great analysis of detecting voter fraud with data, check out Development Seed’s take on the 2014 Afghanistan elections).

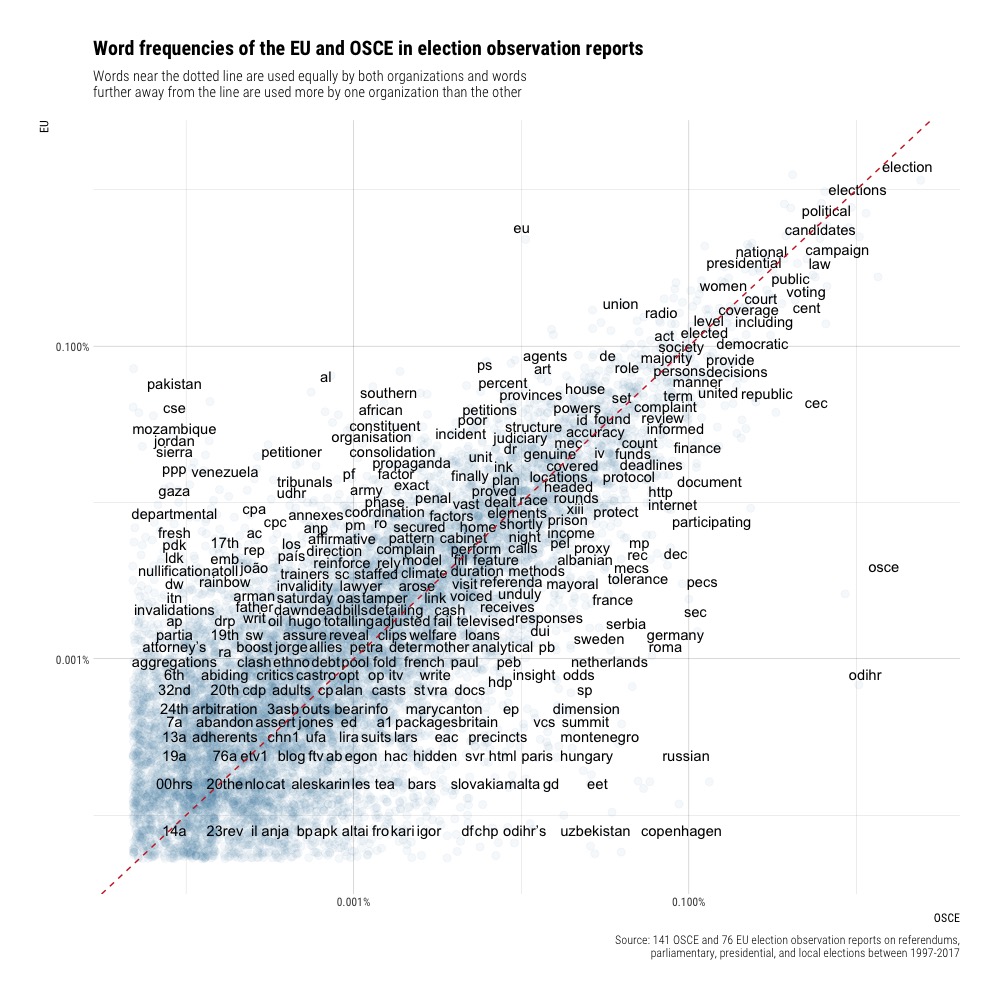

Which words are used more frequently by which election observers?

Adapting code from Julia Silge and David Robinson’s excellent book, Text Mining with R, we can look at word frequencies in the final reports of EU and OSCE election observers.

There are a few things which stand out. First, the most frequent words used by each organization often refer to countries where only they observe elections. For example, since the OSCE’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) only observes elections in OSCE participating states, we see a lot more European countries (France, Germany, Sweden, Netherlands etc.) used by the OSCE; for the EU observation missions, we see more non-European countries (Pakistan, Mozambique, Jordan, Venezuela, etc.). We see that the EU references the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) more frequently, whereas the OSCE references “Copenhagen,” as in the OSCE Copehagen Document, an agreement made by OSCE states on the “rulebook” for democratic elections and human rights.

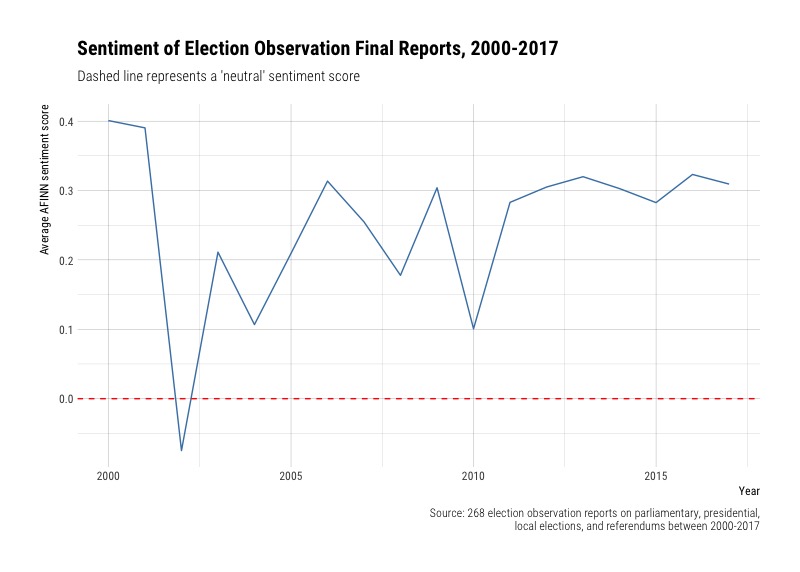

Tidy sentiment analysis

We can again use code from Text Mining with R to help us do sentiment analysis. What is the overall sentiment of election observation reports?

The overall sentiment of election observation reports is on the positive side. We see a sharp decline in sentiment only in 2002 - let’s see which elections were observed that year:

# A tibble: 237 x 4

# Groups: year [18]

year country average_sentiment words

<date> <chr> <dbl> <int>

1 2000-01-01 China 0.54426230 610

2 2000-01-01 Croatia 0.19282511 446

3 2000-01-01 Mexico 0.40631579 950

4 2001-01-01 China 0.51297405 501

5 2001-01-01 Nicaragua 0.31096774 775

6 2002-01-01 Bahrain 0.21126761 426

7 2002-01-01 Ecuador 0.03846154 260

8 2002-01-01 Macedonia -0.22071636 1033

9 2002-01-01 Pakistan -0.07545165 941

10 2003-01-01 China 0.89238845 762

# ... with 227 more rows

We see that there were elections in Bahrain, Ecuador, Macedonia, and Pakistan in 2002, with negative sentiment scores for both Pakistsan and Macedonia, which brought the overall average score down for that year. The 2002 elections in Pakistan were the first multi-party contest, held under close military scrutiny, and the elections in Macedonia were marked by instances of violence and threats and attacks on media (despite these shortcomings, the OSCE concluded that the Macedonian elections met its standards).

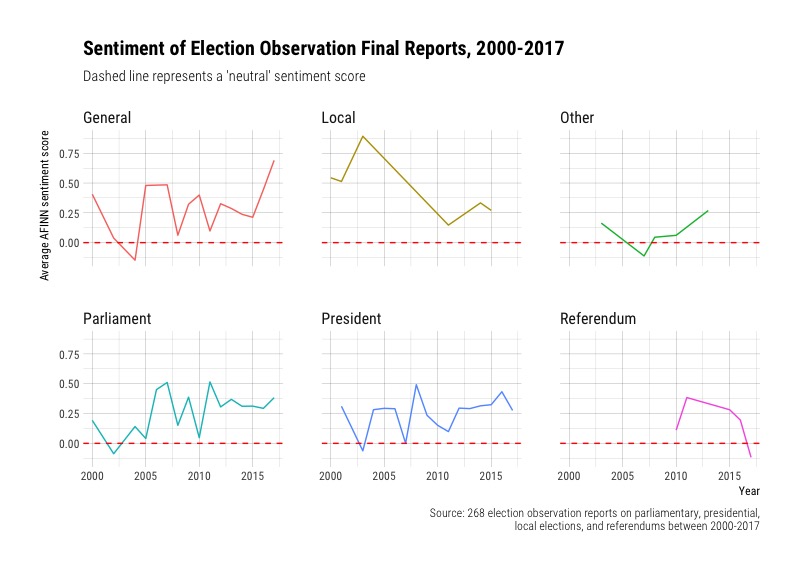

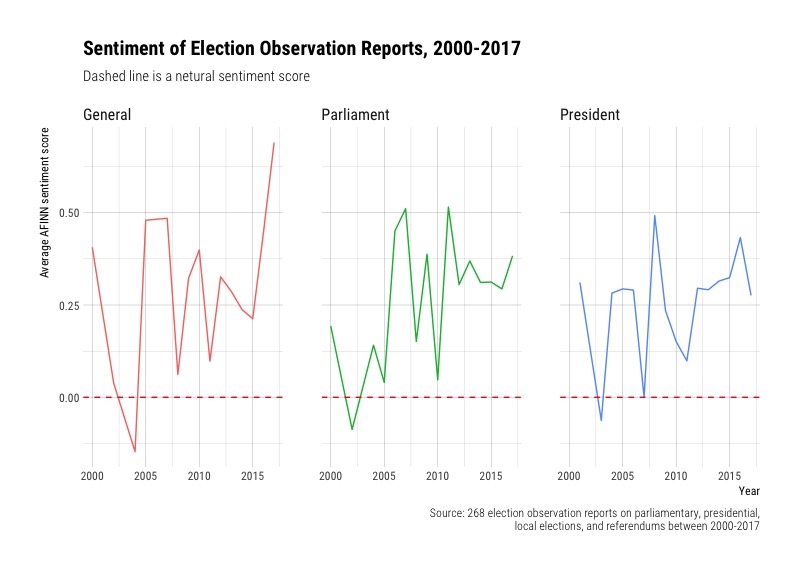

When anazlying sentiment, we can also facet by the type of election. (I should note here that I had some difficulties with classification; a good number of election reports covered multiple elections like paralimentary and presidential, which I grouped into ‘Other’).

Faceting by all types of elections is a little messy, so let’s filter and look at the sentiment fo reports for only general, parliamentary, and presidental elections.

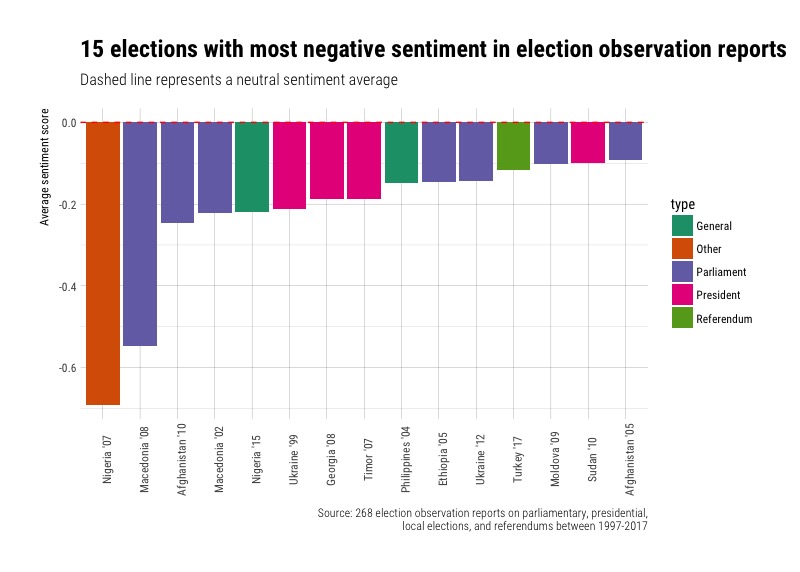

What were the election reports with the most negative sentiment?

We can also look at the elections where election reports were the most negative and the type of election.

We see that parliamentary elections make up the bulk of reports that are the most negative. If we take a closer look at the elections in question, we also see that they were usually marked by military or ethnic violence (Nigeria ‘07 and ‘15, Macedonia ‘02 and ‘08), voting irregularities and ballot stuffing (Aghanistan ‘10 and ‘05), bias by state media and misuse of state resources (Ukraine ‘99, Philippines ‘04, Turkey ‘17), and more.

Conclusion

Overall, I’m pretty happy with the results of this analysis. I think in the future, I would like to refine the categorization of elections to end up with fewer “Other” types, and to add more election reports by non-governmental organizations (like The Carter Center). I would also do a bit more in-depth analysis of words that may refer to different forms of fraud (other than just “fraud” as a term alone - so words like “irregularities,” “ballot stuffing,” “intimidation,” “vote buying,” etc.). I learned quite a bit during this first project: how to scrape PDFs; read them into a dataframe and use tidytext to unnest the text; some trickier work with regex on the filenames to create other variables; and quite a bit about how to use ggplot and faceting.

Photo: “EU Election Observation Mission in Tunisia,” Ezequiel Scagnetti © European Union, (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).