Nationalist netizens, cyborgs, and bots

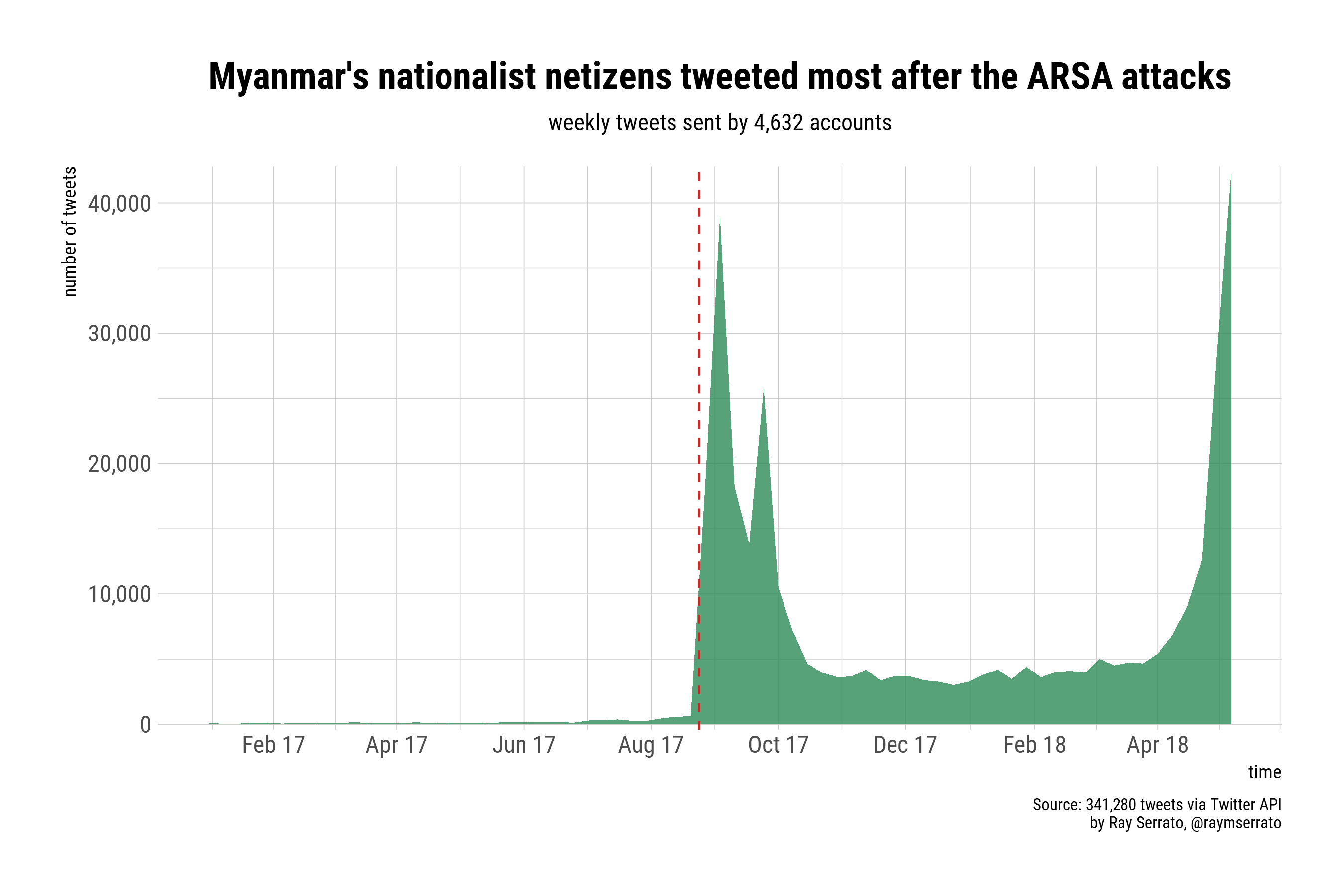

In August last year, militants from the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) attacked police outposts in Myanmar’s Rakhine State, triggering a massive military response and the current crisis. But alongside the military’s campaign to drive ARSA out of Rakhine, another campaign was also underway, this one in social media. In the days following the attacks, I tracked a surge of new Twitter accounts that were using the hashtags, “#Bengali #terrorists,” to distribute disturbing images from the conflict - mutiliated bodies, tasteless cartoons, and other images - and blame the Rohingya people at large for the attacks on the police. My findings were reported in The Irrawaddy and covered elsewhere.

But the vitriol aimed at the Rohingya was not quite new for many people familiar with Myanmar’s social and ethnic politics, and Myanmar’s nationalist netizens number in the tens of thousands on Facebook. But it was perhaps the first time that nationalist groups in Myanmar had taken to Twitter in an attempt to influence the international perception of the conflict.

For some months, I followed one prolific account, @AshinLay1970, which was a main source of hate speech against Muslims and the Rohingya. I’m not quite sure when, but maybe a month ago the account was suspended, presumably for violating Twitter’s Terms of Service. The account had a Myanmar following of a few thousand before it was deleted, but it seems to have been reincarnated, this time as @ashin_asian. The account primarily tweets anti-Muslim and anti-Rohingya content, but it also takes some time to tweet about other right-leaning agendas in Europe and the United States, as well as against policies like the Iran Deal.

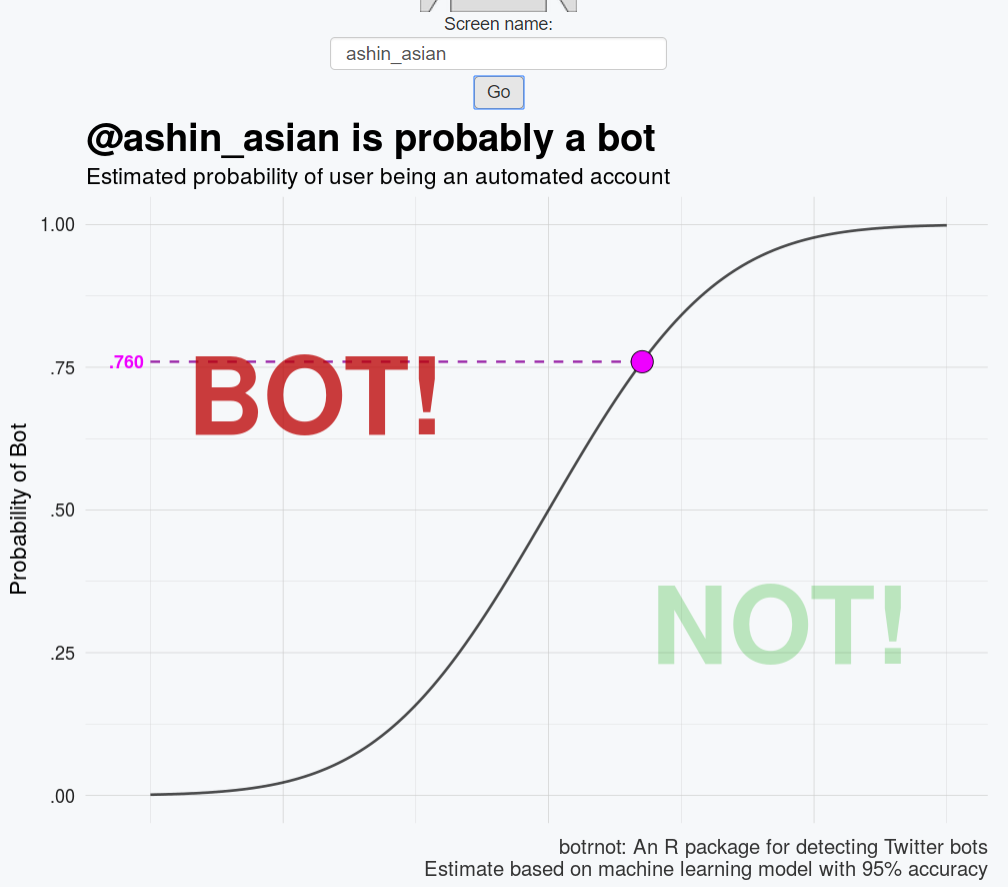

Like @AshinLay1970, I suspected that @ashin_asian was a bot, or at the very least a “cyborg,” an account that is curated by a human handler. To get some sense of how bot-like the account was, I used {botrnot}, which is an applicaiton developed by Mike Kearney, a professor at the University of Missouri. (As an aside, I think his R package is one of the best machine learing tools out there).

Using {botrnot}, we see that there’s there’s a high likelihood that @ashin_asian is indeed a bot. We can also use the {botrnot} package in R to look at @ashin_asian’s followers and determine if they form a bot network to amplify his tweets.

library(rtweet)

library(lubridate)

library(tidyverse)

library(hrbrthemes)

library(scales)

#get the account's followers

ashin_followers <- get_followers("ashin_asian", n = 2000, parse = TRUE, retryonratelimit = TRUE)

#lookup their information just to have it

ashin_followers_info <- lookup_users(ashin_followers$user_id)

#filter followers to only those with more than 100 tweets

ashin_followers_filtered <- ashin_followers_info %>%

filter(statuses_count >= 100)

#get follower timelines

tmls<- vector("list", length(ashin_followers_filtered$screen_name))

for (i in seq_along(tmls)) {

tmls[[i]] <- get_timeline(ashin_followers_filtered$screen_name[i], n = 100)

## assuming full rate limit at start, wait for fresh reset every 170 users

if (i %% 170L == 0L) {

rl <- rate_limit("get_timeline")

Sys.sleep(as.numeric(rl$reset, "secs"))

}

## print update message

cat(i, " ")

}

## merge into single data frame

tmls <- do_call_rbind(tmls)

#run botrnot on the followers

data <- botrnot(tmls)

Asia’s bot problem and Myanmar

There has been an explosion of dubious Twitter accounts across Southeast Asia, and many news reports about what these bots could mean for the region. I spoke to a few media outlets about the phenomenon, and I also co-authored a study on the topic with colleagues in Sri Lanka.

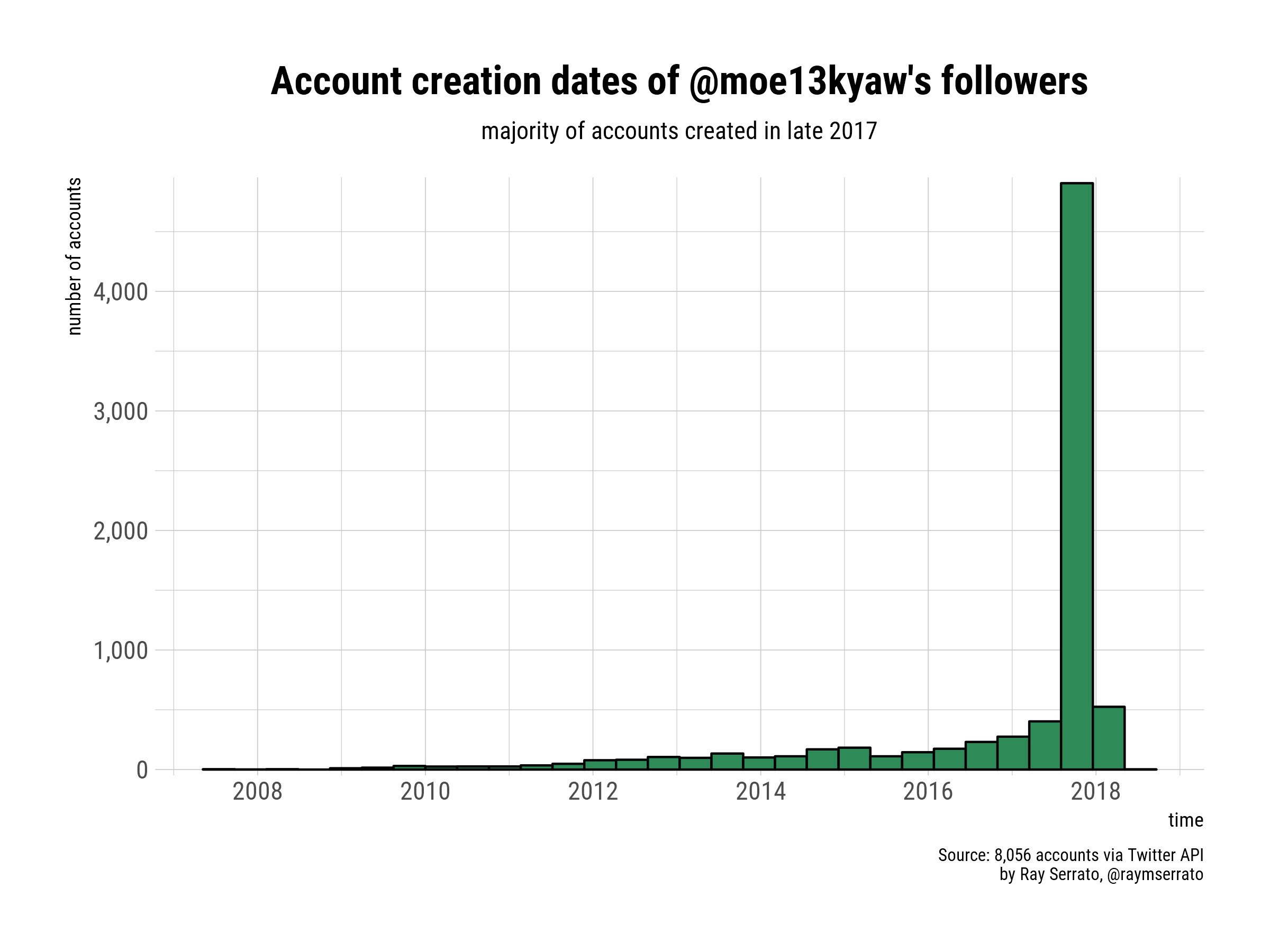

But recently, Victoire Rio wondered if one of her followers was one of these bots and if it was now coming to life. Victoire Rio’s “bot” was tweeting regularly - mostly hateful content about the Rohingya, like @AshinLay1970 - and it had just one follower, an account calling itself Moe Kyaw. I wondered if this was one of the bot accounts, or part of another network of Myanmar nationalists, since the content of Moe Kyaw’s timeline looked awfully familiar. I decided to investigate a bit further by scraping Moe Kyaw’s followers and taking a look first at when the accounts were created.

Many of the accounts were created in late 2017, probably after the ARSA attacks, and they are probably also part of the network I identified back then. There was also another large number of accounts created in 2018, and they may be part of the recent Twitter bot wave. But I also wondered how active the accounts had been since 2017, so I scraped almost 350,000 tweets from Moe Kyaw’s followers, first by looking at just those accounts with “Myanmar” in the location section of their profiles, and then by looking only at accounts with more than 100 tweets.

We see that the accounts tweeted most right after the ARSA attacks, and then we see another burst in April, which is probably explained by the new, dubious accounts joining the fray in April. Generally, the accounts sent almost 5,000 tweets each week between August 2017 and May 2018. But the actual number of sent tweets may be higher because, in the interest of time, I only scraped the most recent 100 tweets from each timeline. (I plan to update later with more tweet data - scraping as I write this).

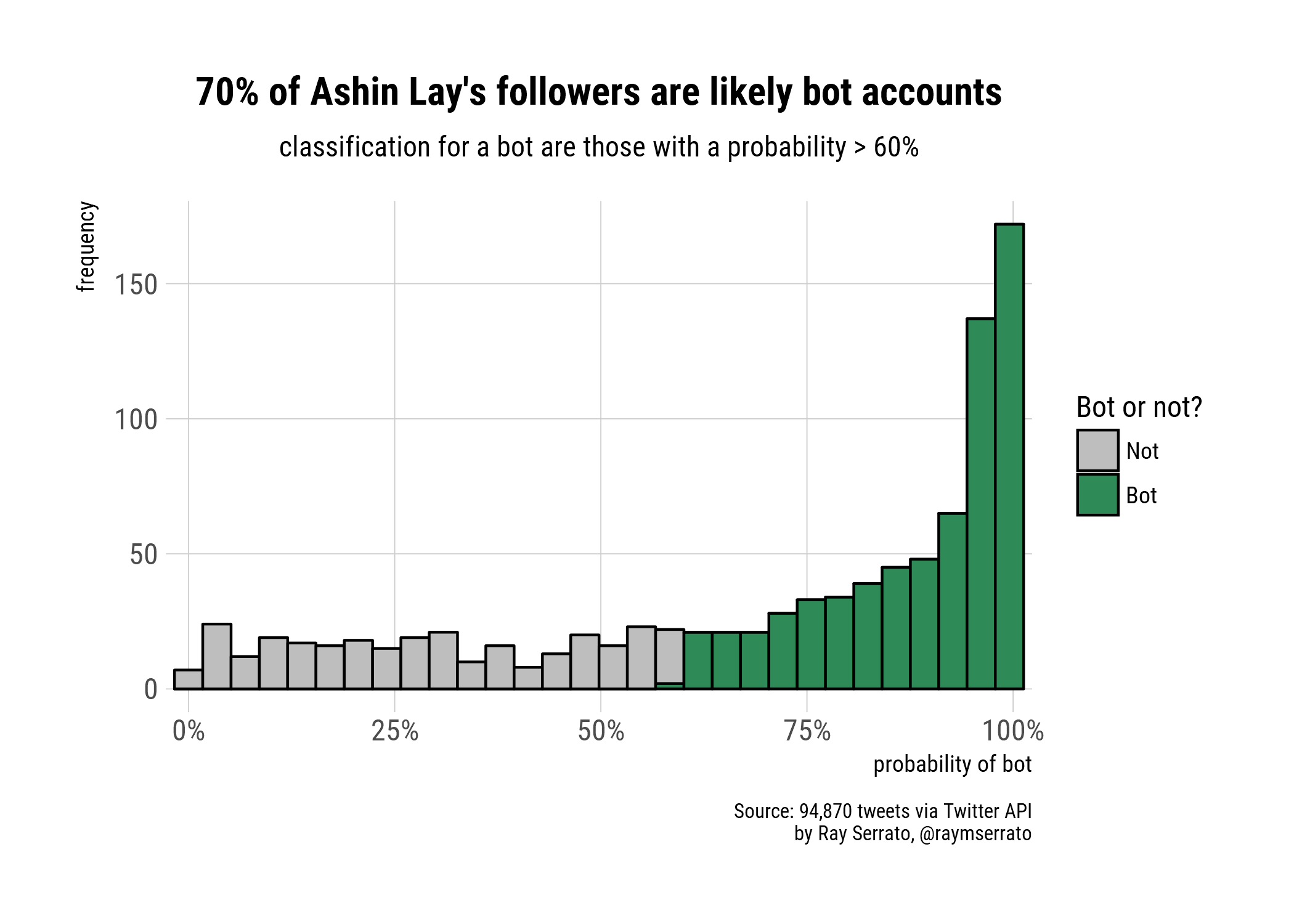

Finally, when looking at the {botrnot} result for 2,503 of the accounts (or around half), I found that a whopping 87% of accounts were classified as bots. I am a little skeptical of this result and I wonder if there are some features of these accounts that makes {botrnot} assign so many of them high probabilites. For example, many of the Myanmar-specific accounts have tweeted infrequently (and when they have, they have mainly retweeted content), they have few favorites and followers, as well as less time on Twitter. Some of the accounts have actually not tweeted at all since September 2017. This leads me to believe that many of them are indeed nationalists that crossed over from Facebook, and only few of the accounts - like AshinLay or Moe Kyaw - seem prolific enough to be bots.

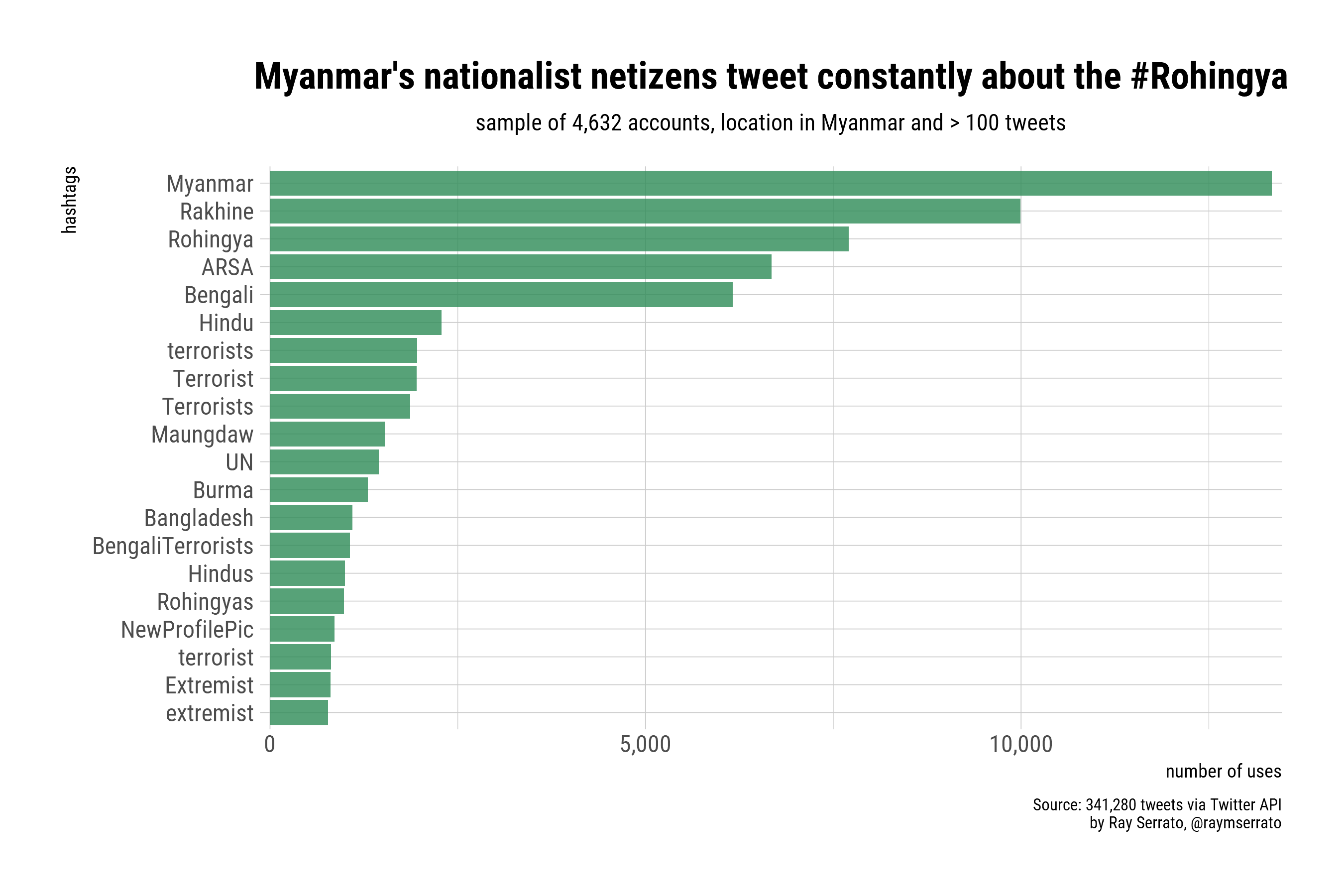

One last thing we can do is take a look at the hashtags the accounts have used, which can help us understand what they are tweeting about. (This is probably the most unnecessary analysis so far).

Closing thoughts

There were many fears that the recent explosion of suspicious Twitter accounts in Asia would be weaponized. If my initial analysis is any indication, some of the accounts are already getting to work. These accounts may turn out to be bots or cyborgs or even real people who want to shape a particular narrative. It will be important to find out more about the provenance of these accounts. But for people who care about truth - which seems a bit strange to write in our time of post-truth politics - it will also be important to refute disinformation and to have compelling counter narratives, especially against ideas or agendas that want to divide us.